January 2011

So many product research projects focus on influencing a decision, for which the researcher provides very specific insights about a specific portion of the overall problem.The beauty of Participatory Design projects is that the focus in not only on the initial task-at-hand that needs to be solved by the group, but also that the unstated goal becomes raising the knowledge of the people in the room.

When engaging in formative, strategic research for my product teams, and by engaging them throughout the process, my goal is to inform my stakeholders about a broader, more holistic context of use.

I hadn’t thought about this particularly, until a design director at work said to my director, “I want to work with you. But my people can’t focus on anything but research that helps them design what they are working on right now.” [Read into that “can’t” what you will] His meaning was that I can’t spend time sharing insights with the designers that don’t directly answer questions about this widget or that widget. Very disappointing. Especially when I’ve developed good relationships with the Product Managers, Marketing Managers and Engineers by sharing stories and insights about user experiences that helps to raise there OVERALL understanding of how people use communication tools.

My purpose for this kind of sharing of insights is mainly driven by my belief that I am not at MOST of the meetings where decisions are made– if they are even made in meetings. I also can’t research every little question that comes up, “Should this button go here or here?” “Do people share photos or quotes more often?” Therefore I need to arm the decision makers with an empathy and understanding of how different users make choices, so that EVERY decision they make is a bit more informed by real end-users.

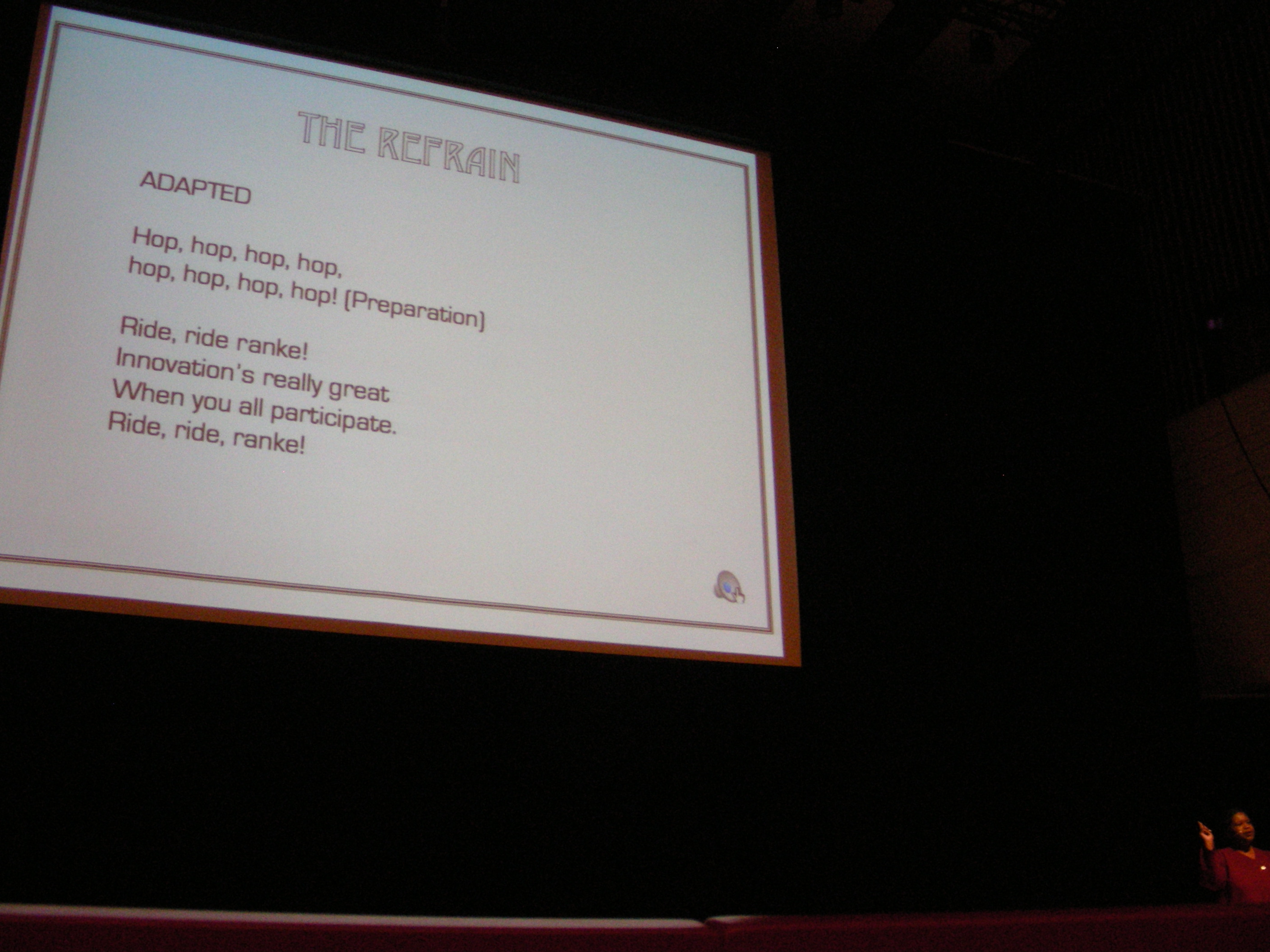

I had the pleasure of attending the Participatory Innovation Conference (PINC) at the University of Southern Denmark on January 12, 2011. Dori Tunstall gave a remarkable closing keynote in which she performed a demonstration of three phases that design research/design anthropology/participatory design/user-centered design have evolved through in the past few decades. It was helpful to have her perspective on the key transitions:

I had the pleasure of attending the Participatory Innovation Conference (PINC) at the University of Southern Denmark on January 12, 2011. Dori Tunstall gave a remarkable closing keynote in which she performed a demonstration of three phases that design research/design anthropology/participatory design/user-centered design have evolved through in the past few decades. It was helpful to have her perspective on the key transitions:

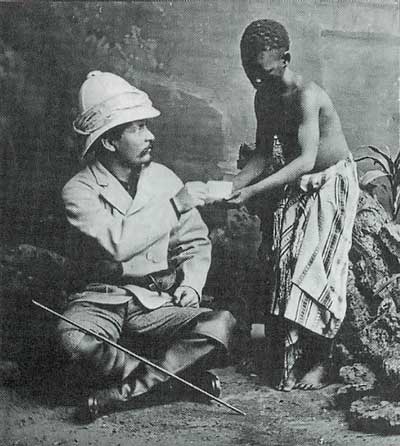

– In the beginning, design anthropology was about researchers as interpretive experts, delivering and recommendations to design teams and others.

– In the 1990s this evolved toward Participatory Design in which interdisciplinary teams participated in observations and defining insights. Insights are delivered in the form of experience models and personas. Researchers become facilitators with multiple, complex stakeholders involved.

– She proposes that the next phase of Design Anthropology will establish the academic foundation of this practice. With that will come a focus on social issues and an understanding of how objects affect the people around them. Designs are disruptions to the people in a culture and those disruptions should be studied. This study of objects and processes define what it means to be human. Design can seek to close the gap between the disruption and the ideal experience.

Dori is now establishing a program at Swinburn University in Melbourne, Australia. It seems to be a program that comes closest to the practice of Design Research as it has developed in the U.S., because of the focus on developing expertise and understanding around studying people and the objects and processes that they use.

From the website:

The purpose of the Master of Design (Design Anthropology) program is threefold:

She recommended some resources that help define this most recent stage of Design Anthropology, and her own work:

- Thinking of Things by Esther Pasztory (2005)

- Collective Joy by Barbara Ehrenreich (2007)

- Transmodernity by Rasa Maria Magda (2004)

- Linda Tuhivai Smith’s (1999) critique of how we conduct research in cultures

Many conferences have been conducted on this topic. Well, not directly (that would probably be more helpful). But Anthropologists do enjoy centering discourse around who should and should not be conducting research. I have since forgiven EPIC for the first Ethnography in Praxis Conference during which a near fist-fight that broke out over who “owns” ethnography. And EPIC has been much more welcoming toward design researchers since. But what EXACTLY are they defending? It’s very difficult to know what you don’t know. So us “outsiders” are often still in the dark. But the truth is, we can learn a great deal from the ethical and bias-lessening techniques of Anthropologists and Psychologists.

Many conferences have been conducted on this topic. Well, not directly (that would probably be more helpful). But Anthropologists do enjoy centering discourse around who should and should not be conducting research. I have since forgiven EPIC for the first Ethnography in Praxis Conference during which a near fist-fight that broke out over who “owns” ethnography. And EPIC has been much more welcoming toward design researchers since. But what EXACTLY are they defending? It’s very difficult to know what you don’t know. So us “outsiders” are often still in the dark. But the truth is, we can learn a great deal from the ethical and bias-lessening techniques of Anthropologists and Psychologists.

Many universities offer Psychology 101, and I think all Design students should take this, but few offer Anthropology 101. As a result, the fundamentals of Anthropolgy and Cultural studies have eluded me for the first 10 years of my career as a design researcher.

Last week, literally while in the middle of an ethnographic observation, I stumbled upon a book that helped tremendously. I was observing a college student, and during her two-hour homework session in the library, I needed something to occupy my attention, to remove some of it from the back of her head. I wandered over to the Education section (because it was fairly close) and found a book by Rebeka Nathan, “My Freshman Year: What a Professor Learned by Becoming a Student.” This book caught my attention because of the topic, but after reading her introduction, I flipped next to the back of the book, where the author reflects on the ethical dilemma of conducting research under cover. I learned from her discussion the careful ethical considerations that Anthropologists are taught that helped me to add integrity to my own research.

– Misrepresenting oneself to the culture being studied is inherently disrespectful. This was interesting to me, because often we do not want to reveal what the focus of our research is. So this discussion made me step back to make sure that I am not pretending or lying in my current research. I am not revealing the company that I work for to my participants, to help prevent bias, but I have been clear with them upfront why that is. In fact, my LinkedIn profile currently states that I work for “An Internet Company in Silicon Valley” and I point participants to that for credibility.

– Obtaining information under false pretenses. This sounds evil, but it can actually happen quite easily. For example, my participant had a Skype conversation with her best friend while I was observing her. I sat in the room, but was generally out of view of her friend. My participant did not point out my presence to the friend, and I wanted to observe a conversation as naturally as possible. But because that friend did not know that the conversation was being “recorded” (only note taking), I cannot ethically use the content of the conversation in my research. I will record the fact that it HAPPENED. But I won’t use quotes from it.