September 2009

Our team has been talking about the steps of turning concepts into prototypes, and prototypes into tangible ideas. One interesting problem, and one insight arose from the discussions.

First, as a team, we can conflate the two important questions that we have about our concepts, and it can confuse and complicate our user research on the hospital floor. As we seek to understand whether the idea we are exploring is worth pursuing, we need to understand two distinct questions:

– Is this concept worthwhile?

– How would it work?

When we take a prototype onto the hospital floor and we don’t know whether we are trying to understand whether nurses are enthusiastic about the idea, or if it would really he helpful or how the idea could be implemented on the floor, we have trouble asking the important questions and understanding exactly what we are learning from our time on the floor.

So we are making extra effort to make sure that we separate out those two purposes. Testing whether the concept is worthwhile is a combination of both direct questions to nurses about how interested they are in the solution, as well as prototype tests that have observable outcomes, such as fewer patient requests or longer conversations between nurses and patients.

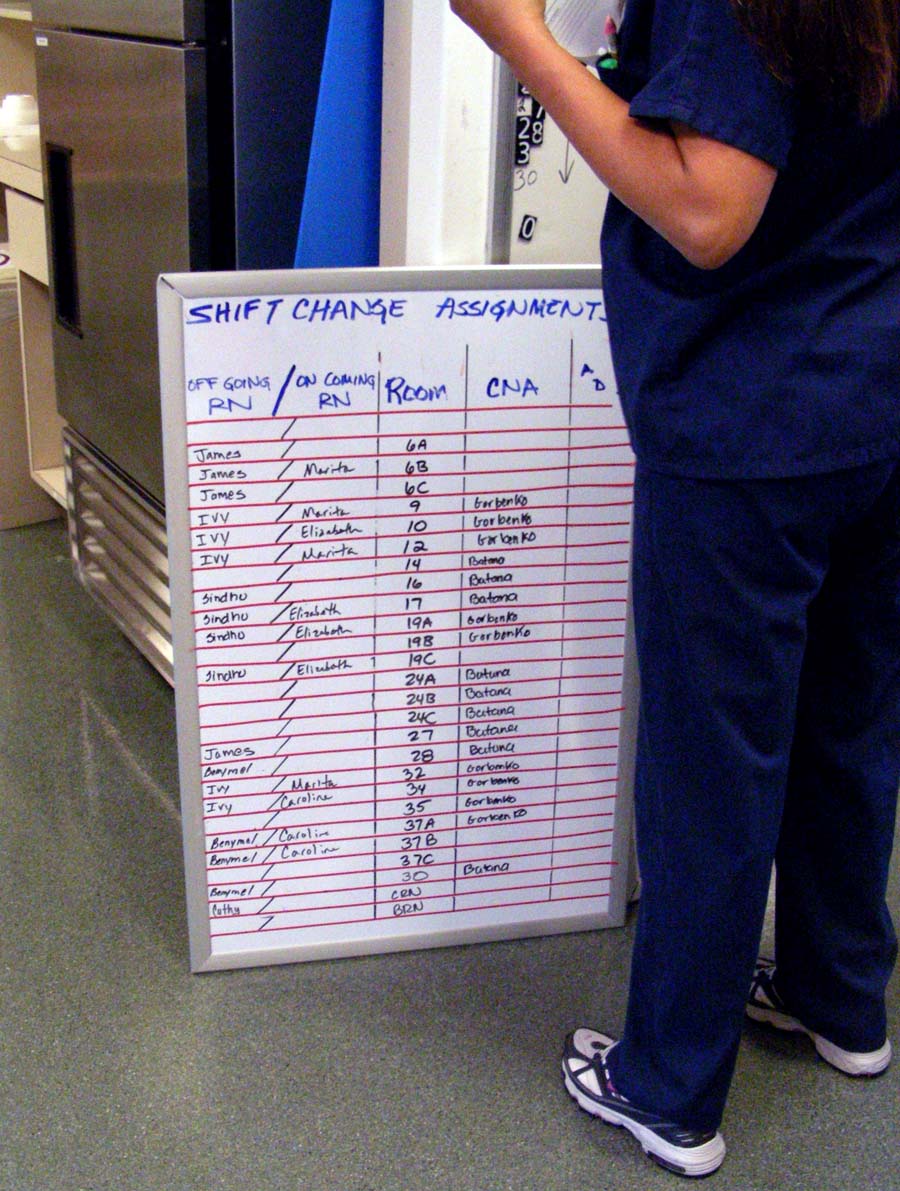

“How would it work?” is more of an investigation question. It takes a lot of legwork to understand the logistics of how a concept can be implemented on the floor… who answers the phones at shift change? How do nurses find the phone numbers they need, etc. But then it needs to be followed up with prototype tests that prove or disprove the methods for making it work.

A new way of working for us.

We are working with an expert client, they have worked with our design firm for a long time. We helped them develop their own innovation process that they have used for years. As we train six new hires, I am finding that we are moving beyond out typical tool set for teaching clients to be human-centered designers. I want to branch into tools for Participatory Design, but we need to make them up as we go.

But it’s tricky. It’s a more difficult learning process to learn design and participatory engagement, because new designers most often want to hold on tightly to the process, not open it up for the unpredictability of people!

For our project, in particular, the finesse required to walk onto a hospital floor and ask a nurse to help solve a problem, is more difficult. It is easier to make a plan in the team room. Bring that plan to a nurse and say, “We’d like you to try X. And if you try X, Z might happen. We’d like to find out what would happen.”

The interaction is less predictable, less controlled, if you walk up to a nurse and say, “We have heard from nurses that Shift Change is stressful and chaotic. We would like to find out how Shift Change would be different if all of the patients were sitting up. Could you help us try this out? What do you imagine would happen?”

How might we help our clients trust the value of showing vulnerability to our users?

In this current project, I am tasked with teaching a client team of newbies how to move through a user-centered design process, WHILE innovating on a real problem in the context of a hospital.

This has made the client team obsessed with doing everything “right.” They want to do as many observations as quickly as possible with exactly the right people. Which is great, but are they paying attention?

Mindfulness is something that we want from the nurses we are designing for. Being present when they are with patients. But is our team *present* when they are in an interview or observation?

We tested them.

For our weekly learning session, we took them off site. Away from their post-its, away from their notes. And asked them to describe some of the key nursing activities. We had other motives as well. Their concern for getting enough done made them question how well they were doing. My teammate recognized that observing in a hospital can make anyone lack confidence. And what this team needed was a chance to recognize how much they had learned.

They were surprised! They didn’t know how much they knew. They were proud of themselves when they saw how much they had learned. And getting off-site for a day was an important refresher at the beginning of another week in the hospital.

Now, as we head into Synthesis, we have planned a daily “Top of Mind” session at 9am, for the whole team to sit down together and talk about the ideas and patterns that are standing out to them as most interesting. This will hopefully remind everyone to be mindful of the work they are doing, we hope they will always be able to describe– without notes- what is most exciting about the evolving information.

Our design team brought our first prototypes into the field for testing with nurses and patients. We are starting slowly. 4 small prototypes, 2 hour sessions.

We started with nurses who know us and are engaged in the project. But still, it is intimidating to bring foam core and markers onto a working hospital floor to interact with people who are very sick. Which is why, for these first concepts, we are using a “resource nurse.” We have hired an extra nurse for a full shift who can either test the ideas him/herself, or can duplicate the work done by the nurse who is testing our concept.

For our first concept, Tom, our resource nurse, tested out the “Understanding Globe.” This concept asks nurses to spend 5 focused minutes with each patient, supported by 5 broad questions that ask patients how they are, and a globe that is on a timer, it glows softly for 5 minutes. When the globe stops glowing, the nurse has a graceful cue to conclude the conversation and continue on with her/his other tasks.

Tom chose one nurse working on the floor and asked her if he could meet with each of her patients, to try out this concept. Sonya gave Tom a brief description of each of her 5 patients (very brief, she was running behind on meds). Tom then introduced him to the first patient, explained that he was trying out a new idea, and began the conversation. When the globe turned off, he gently ended the conversation and said good-bye. He repeated this with 4 more patients. Tom really enjoyed the activity, but he is a nurse who enjoys taking time with patients.

Our real proof of concept will come when Tom needs to work this into his regular workday, and when a nurse who typically rushes through patient interactions in order to complete an ever-growing task list, can actually see the value in 5 focused minutes with patients. But first things first.

Tom discovered that two patients were having problems with their pain medications. One was not receiving doses in time to stop the pain. Another was having an adverse reaction to the pain medicine, terrible headaches. His nurse hadn’t taken the time to explain the side effects of the pain medication, so Tom followed up with his nurse to switch the prescription. Additionally, a woman with a recent MS diagnosis was having a hard time dealing with the emotion of it. She told Tom she talks to her husband about it, but Tom suggested she might also meet with the hospital social worker. And Tom made a phone call to set that up.

Our prototypes will be measured in pilot tests, with Time & Motion studies and other metrics. While we are out in the field refining our concepts we need to keep our eyes open for potential clinical measures of success, and customer satisfaction is not one of them. We may be able to measure the success of this concept by tracking additional referrals to other services and better pain management programs. Eventually with the hope that both of these will lead to faster recovery times and shortened stays in the hospital.